Path Dependency and the Maiming of the Biomedical Research Enterprise

How fear mongering, undiscerning policies and an obsession with animal testing stifled innovation and shortchanged the discovery process

by

When prior decisions dictate future actions by limiting available options to a handful of suboptimal choices, economists call this phenomenon ‘path dependency.’

We tolerate instances of path dependency in healthcare, technology and politics quite well, often with little awareness of their constraints or even existence. For instance, the QWERT sequence on keyboards, designed initially to reduce mechanical jams, is a holdover from the typewriter era. The identical layout was adopted in the digital age, ostensibly not to spook consumers and jeopardize future sales.

But not all cases of path dependency are benign. Animal testing - an eonian path dependency - is an ongoing reminder of the generational harm a society endures because of past decisions too difficult to rectify. Indeed, path dependency associated with animal testing has proven to be among the hardest to overcome.

Case in point, despite their poor value in predicting toxicity in humans, animals have been relied on ubiquitously for such purpose at least since 1938, the enactment year of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Federal FD&C Act) - a set of U.S. laws that sanctioned animal use in drug development.

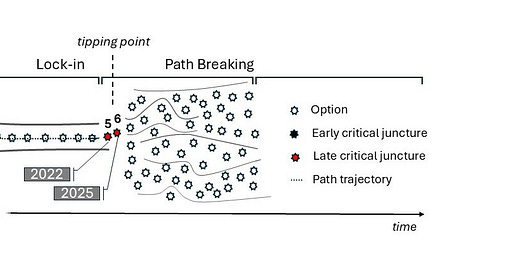

It can be argued that members of the scientific elite duped the U.S. Congress twice - once in 1938 and then in 1962 (Diagram, n° 1 and 2, discussed thereafter) - into an alliance that rendered the American biomedical research enterprise inorganically linked to experimentation on animals. Forecasting human response using animals was presented to lawmakers then as the ideal solution to hedge against health risks, without sufficiently explaining the disparate and often misleading nature of artificial animal models.

In brief, that spurious alliance sought to forcibly fit a square in a round hole. In doing so, it strangled, through statutes nonetheless, any ‘outside-of-the-animal-box’ thinking in discovery research. To that extent, the exclusive reliance on animal testing translates today into irrecuperable delays in the development of medicines, missed opportunities due to misguided regulatory principles and exorbitant costs ultimately passed onto consumers.

Previously, we argued that an externality like an intervention by DOGE, the Department of Government Efficiency established in 2024 to eliminate government waste and promote efficiency, might be the needed tipping point to fix this stubborn issue of animal testing in drug development, given the billions in wasteful spending on misleading, irreproducible science.

“We have moved away from studying human disease in humans. We all drank the Kool-Aid on that one, me included,” said former NIH Director (2002 -2008), Elias Zerhouni. “With the ability to knock in or knock out any gene in a mouse—which can’t sue us, researchers have over-relied on animal data. The problem is that it hasn’t worked, and it’s time we stopped dancing around the problem…We need to refocus and adapt new methodologies for use in humans to understand disease biology in humans.”

The rise of animal testing to what regrettably became the catch-all test in modeling human health and disease is the outcome of several ‘critical junctures’ - defining moments in the genesis of any path dependency that shape it into its rigid, needlelike trajectory. This narrowing of options prevents the consideration of better, more efficient alternatives.

In our analysis, three early critical junctures forced biomedicine to become reliant on animal experimentation - two were established by U.S. laws (1938, 1962) and the third resulted from a catastrophic investment decision (2006) by the federal agency in charge of scientific research, the NIH itself. Similar actions caused environmental health assessments to be dominated by animal testing (e.g., the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) of 1976) but this aspect is not expanded on here for brevity. Appreciating the context of these junctures can help us design rational and better solutions going forward.

Notably, a critical juncture emerged of late with the passing of the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 (FDAMA 2.0), a U.S. law since 2022 (Diagram, n° 5). This momentous reform, alongside FDAMA 3.0, a related legislation, is poised to cut waste in research, advance a humane agenda in science and liberate the drug discovery process from its restrictive, animal-centric deadweights.

Triggering path dependency in 1938

The first critical juncture can be traced back to 1938 with the enactment of the abovementioned Federal FD&C Act. In the prior year, a poisoning incident (known as the Elixir Sulfanilamide incident of 1937) was sufficient to push lawmakers into accepting animals as the ‘guinea pigs’ in testing toxicity of experimental drugs. Such requirement was incorporated in haste in the newly minted Act, which also gave near unlimited authority to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to oversee the regulation of food, drugs and cosmetics in the United States.

Of note, the toxic chemical behind the 1937 Sulfanilamide poisoning cases (Diethylene Glycol or modern-day antifreeze) can be found harmful using almost every credible animal-free toxicology method. To be clear, animals have markedly different if not misleading toxicity patterns compared to humans. They provide little de-risking value were they to be the safety gatekeepers of human drugs. Elixir Sulfanilamide tragically poisoned around 100 people in 1937, but Vioxx, an arthritis drug approved by the FDA in 1999 and cleared in preclinical stages using animals caused a disaster - the death of nearly 100,000 individuals by 2006.

The roster of deadly FDA-approved drugs includes the antidiabetic medication Troglitazone (Rezulin), the anti-inflammatory drug Valdecoxib (Bextra) and the pain medication Bromfenac (Duract). In actuality, one-third of new drugs on the market had safety problems after FDA approval.

Fortifying path dependency in 1962

The second critical juncture occurred with the passing of the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments to the Federal FD&C Act in 1962. An experimental drug must now show efficacy and be examined for side effects - in animals - before it can proceed to clinical trials. The trigger for such requirement was, in turn, another international public health outcry after the drug Thalidomide, prescribed to pregnant women for morning sickness, caused birth defects in the 50s and 60s.

But again, Thalidomide does not cause birth defects when given to pregnant rats and mice, the most used laboratory animals. Scores of similar classes of drugs would be missed in animal screening and erroneously deemed safe. The acne medication Isotretinoin (Accutane), on the market from 1982 to 2009, caused increased risk of birth defects, miscarriage and premature deaths among pregnant women who used it. Animal testing did not predict nor prevent the Accutane tragedies.

The Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments, alongside the 1938 toxicity rules imposing animal testing, were sincere yet misguided attempts at establishing rigor. Their main accomplishments as knee-jerk legislations were to shape drug development into the inefficient paradigm it is today.

To the regulatory health agencies, adopting animals to be the ‘gold standard’ was an attractive proposition, especially in 1962. It enabled administrators to ‘kill two birds with one stone,’ (i) make the alarmed public believe that drug safety is now under control, and (ii) bolster the interest of the pharmaceutical industry of which the discovery portfolio was increasingly focused on developing robust animal research pipelines. As a reminder, the prestigious U.S. National Academy of Sciences, through a series of publications, was touting as early as 1960 “Animal Models in Drug Development” as the new frontiers of biomedicine.

In hindsight, such reasoning led to the ‘productivity crisis’ in the pharmaceutical industry (reviewed here). Today, a jarring 90-95% of experimental drugs fail in human trials after animal data is used to justify their advancement to the clinical stages. The price tag of trials failure in oncology alone is $50 to $60 billion per year. Each decade, the failure of first in humans (FIH) trials across disease domains in the U.S. costs trillions of dollars. In addition, hundreds of thousands of claims are triggered by harm caused by unsafe but FDA-approved drugs. Litigations related to Vioxx alone cost $3 billion in civil liabilities, forfeiture and criminal fines paid by its drugmaker, Merck Pharmaceuticals.

Locking-in path dependency in 2006

The third critical juncture, and arguably the most damming, is a multibillion-dollar initiative by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to create thousands of mouse models and make them available to study human diseases. The project initially labeled the Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP) envisioned a deletion in every gene in the mouse genome – or roughly 18,000 genes.

But expecting genetically modified mice to teach us about human diseases is like switching to an all-high-fructose diet and expecting to lose weight.

To begin with, only 50% of genes in mice have similarity to humans and 15 to 20 % of mouse genes are embryonically lethal (cause death in embryo), so the endeavor is ill-conceived from the start. Moreover, many genes have varying functions and/or activation patterns at different developmental stages (e.g., embryonic vs adult). Eliminating a gene at the embryonic stage will produce, in those that survive, irrelevant mongrels. Furthermore, gene alterations in mice have long been known to produce dissimilar sequelae and characteristics (called phenotypes) to those presenting in humans - the loss of the cardinal tumor suppressor gene p53 is a prototypical example where tumors unrelated to human cancers arose in mice with p53 loss.

Besides, gene regulation, recombination, silencing, redundancy, compensation and strain variance among the same mouse species, let alone inter-species variability are all critical aspects to consider before producing a single genetically altered mouse model, let alone thousands.

The ‘kitchen-sink’ approach taken by the NIH can be viewed as an example of administrative gluttony - health agencies appropriating exorbitant amounts of taxpayer’s money and spending it on legacy projects. Concomitantly, NIH program level funding swelled from $17.84 to $49.183 billion between FY2000 and FY2023. Still, this is not the most concerning or wasteful damage of all.

The irreparable harm is reflected in the massive dissemination of thousands of artificial mouse models with little relevance to human biology. This act flooded the market with aberrant study models and saturated the literature with misleading, human-irrelevant data. Indeed, NIH-funded mouse models churned up thousands of publishable yet irreproducible preclinical studies, the bedrock of drug target discovery.

The seeming obsession with animal research at the NIH sent investigators on wild-goose chases and normalized - even glamorized - the use of animals in scientific experiments as the supreme, ‘in vivo’ science (in a living organism). This has markedly contributed to the 'reproducibility crisis' and the perceived diminished credibility overall in published studies.

Francis S. Collins, the longest-serving former director of the NIH (2009 – 2021), wrote in the journal Nature in 2014 that “preclinical research, especially work that uses animal models, seems to be the area that is currently most susceptible to reproducibility issues.” Consistently, 89% of preclinical studies, most of which involve animals, cannot be reproduced!

Oddly, it was under Dr. Collins’s leadership that the NIH saw the largest expansion of its animal-heavy programs, including KOMP, for which Director Collins was a founding member. KOMP has evolved after many program expansions (e.g., knockout, transgenic, CRISPR), into a massive conglomerate referred to now as KOMP2 and is part of an International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC). Of note, KOMP launched in 2006 during Dr. Zerhouni’s tenure as NIH director.

When concerned scientists warned against the dependency on animal testing and betting the future of discovery on research in rodents, these voices were belittled, discredited and swiftly dismissed by the establishment as anarchists, animal welfare nuts or fringe scientists.

This NIH-funded endeavor - thriving and well today with high-end facilities worldwide - locked in path dependency (Diagram, n° 4) and fueled the “reproducibility crisis,” which is often referred to poignantly as the “credibility crisis” in scientific research.

Breaking path dependency in 2022

In 2022, a group of no-nonsense legislators infuriated by the inefficient drug discovery paradigm but also the unabated proliferation of animal testing passed the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 (FDAMA 2.0) in the U.S. House and Senate (Diagram, n° 5). FDAMA 2.0 became U.S. law later that same year.

With FDAMA 2.0, lawmakers overturned a century-old rule requiring animal testing in drug development, in favor of human-relevant, technology-driven alternative. Such reform is a critical juncture unfolding in real time.

The FDA is forthcoming about the fact that 92% of drugs tested on animals fail to meet the standards for human use, and this rate is growing, not improving. Paradoxically, to this day FDA has not implemented the policy mandates of FDAMA 2.0 or provided regulatory clarity to drug sponsors on FDAMA 2.0. Such a failure to act on the part of the agency chiefly responsible for implementing drug laws is a good example of government discordancy, if not malfeasance.

In 2023, a bipartisan group of Senators, led by Rand Paul, R-Ky., and Cory Booker, D-N.J., sent a letter to the FDA demanding an explanation for the stultification and an implementation timeline of the enacted law. But no progress materialized.

Not to be deterred - or duped through intransigence this time - a forward-thinking group of senators guided the U.S. Senate to unanimously pass on December 12, 2024, the FDAMA 3.0, demanding that the FDA execute the indivisible implementation of FDAMA 2.0 within a defined timeframe. This bipartisan legislation - that could be a tipping point - was re-introduced (S.355) in February 2025 by Senators Cory Booker (D-NJ), Eric Schmitt (R-MO), Rand Paul (R-KY), Angus King (I-ME), Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), John Kennedy (R-LA), Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), Ben Ray Luján (D-NM), and Roger Marshall (R-KS).

The resistance to implement FDAMA 2.0 is one reason for the new administration to shake up the working of the FDA, NIH and their overseer, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) - a cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government whose motto is "Improving the health, safety, and well-being of America."

Organizations like the Center for a Humane Economy and Animal Wellness Action that championed FDAMA 2.0 alongside their partners across industry, academia, and nonprofit organizations have shown no abatement in their advocacy efforts thus far and will not until the full, clear, and impartial implementation of FDAMA 2.0 is accomplished.

In June 2024, then U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) released a framework outlining potential reforms at the NIH. Many stakeholders have offered ideas on addressing the inefficiencies at the agency. NIH has one of the most dedicated workforce in the federal government system. But one plan, Research Modernization NOW, by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PeTA) truly stands out. It is a comprehensive strategy - a blueprint for eliminating waste and jumpstarting productivity at the key agency. If adopted, the plan could usher in a new era of federal research and serve as a tipping point.

An opportunity for real change

At this juncture, the new administration has the power to curb unreliable approaches, including categories of animal testing that have proven to be grossly misleading, to prioritize technology-driven, human-relevant alternatives. By doing so, it would — in a singular swoop — reduce waste across federal contracts and grants, promote modern drug development, lower healthcare and prescription drugs cost, bolster national competitiveness, improve environmental health and safety testing, and modernize practices within all health and regulatory agencies.

Should the Trump administration, possibly through DOGE, take on the task of weaning America from its reliance on animal testing in modeling human response, the consequences could be historic vis-à-vis trimming waste, streamlining priorities at health agencies, bolstering efficiency in the biomedical discovery space and creating a healthier, more compassionate society. This would benefit all Americans but also the world!